The “2-4-6-8 rule” is ingrained in our minds as anesthesiologists from the very beginning of our training. This guideline is used as a barometer of safety, but what evidence do we have to support this rule? Is prolonged fasting truly safer and at what consequence to the patient? Fasting standards were largely established on anatomic theories and expert opinion and have remained stagnant for half a century. Recently, these recommendations have been reexamined and prompted the liberalization of fasting guidelines allowing for clear liquids up to one hour prior to the induction of anesthesia at several pediatric centers in the United States (U.S.). The international pediatric anesthesia community has largely accepted reduced perioperative fasting in children for some time, however, the majority of pediatric centers here in the U.S. are hesitant to make this change. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia (SPA) have not endorsed the liberalization of perioperative fasting times. To our knowledge, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and Texas Children’s Hospital are the only pediatric centers that currently allow reduced clear liquid fasting prior to anesthesia in the U.S. We share our experience at Texas Children’s Hospital with the implementation of the liberalization of clear liquid fasting.

On 10/1/2019, the Texas Children’s Hospital system implemented reduced clear liquid fasting guidelines with an overall goal of improving quality care and patient satisfaction without compromising safety. Our group was strongly motivated as a result of poor “patient experience” scores on Press Ganey surveys with expressed frustration surrounding prolonged fasting times.

Implementing this change across such a large pediatric hospital system that performs more than 50,000 anesthetics annually presented some challenges. Legal department buy-in, education, and communication were the largest obstacles our team faced. However, each challenge was overcome with support from our Anesthesiologist-in-Chief and Surgeon-in-Chief.

Our new clear liquid fasting policy roll-out coincided with a larger perioperative surgical communication plan. Standardizing patient communication from our many surgical scheduling specialists was vital to a successful process change. Future plans include centralized scheduling across all surgical specialties.

Our departmental quality improvement team examined the incidence of aspiration events from 10/1/2019 to 12/31/2019 and compared the reported safety events from the previous year. Our aim was to demonstrate an equivalent safety event comparison. The quality improvement database is composed of self-reported safety events for all anesthetizing locations, including diagnostic imaging, across our three Texas Children’s campuses. Events are self-reported by the assigned anesthesia provider. We reviewed aspiration events over the 3-month period following our policy change. An aspiration event was defined as prolonged oxygen desaturation < 94%, unanticipated admission post-operatively, or new chest x-ray findings due to a vomiting event under anesthesia.

The year prior to our intervention, there were 57 reported aspiration/vomiting safety events. Only 8 of these events met our defined criteria for aspiration. Known risk factors for aspiration and vomiting events included gastroesophageal reflux disease, developmental delay, emergency cases and obesity. The reported aspiration events from our database did not share any common risk factors. Six out of the 8 events were in patients who had fasted greater than 8 hours. Some patients had no risk factors for aspiration/vomiting. Roughly a third of the events were reported from remote sites (i.e., interventional radiology and magnetic resonance imaging suite).

Upon review, there were 19 total reported aspiration/vomiting events with only one event meeting our above defined criteria for the three-month post-intervention assessment. Our team determined that the events reported were consistent with events reported prior to our reduction in fasting times.

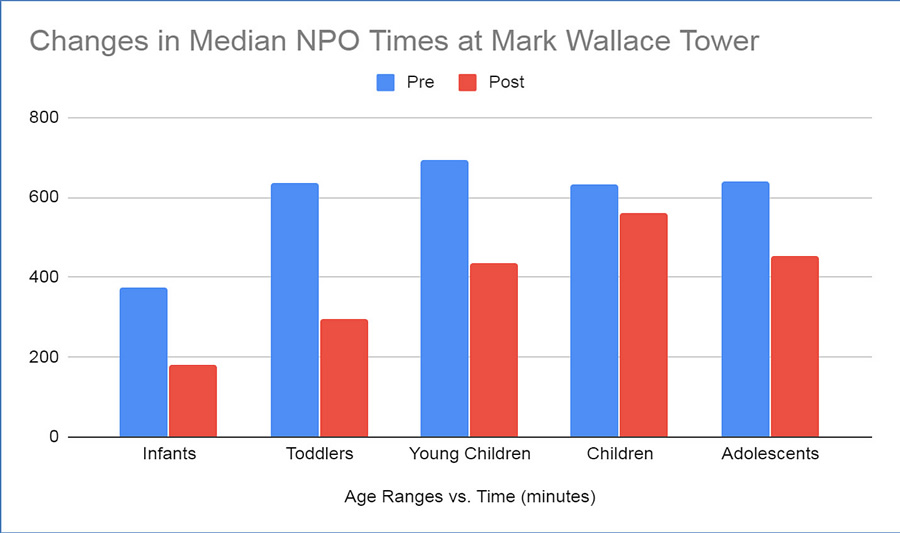

To further mark the success of our policy change, our team examined fasting times for all patients in our ambulatory surgical care site. A clear reduction in median fasting times, particularly in the younger age groups, was demonstrated as shown in the graphics below.

We continue to review aspiration/vomiting events 18-months post-intervention and we have not seen an increase of reported events for our institution. We are happy to report very positive feedback regarding our process change via Press Ganey survey reports.