Overview of Point of Care Ultrasound

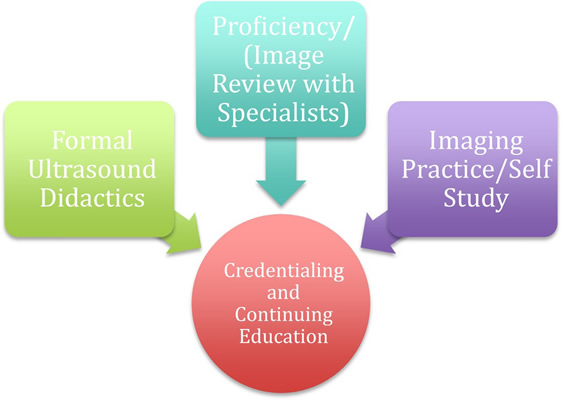

Point-of-care-ultrasound (PoCUS) has become mainstream in a host of acute care specialties owing to a growing list of applications (Table 1). However, despite its well documented use, adoption by anesthesiologists remains lagging with concerns related to lack of training, fear of missing diagnoses, and a lack of a certification pathway[1, 2]. While most of the PoCUS utilization and research has been centered around other acute care specialties (critical care, emergency medicine), there is growing evidence to dispel these concerns provided proper training and oversight. This speaks to the tremendous amount that PoCUS can add to anesthesiology practice.

Point-of-care-ultrasound has emerged as an invaluable tool for real-time physical examination assisted diagnosis with numerous studies highlighting improved accuracy over traditional physical examination[3]. PoCUS requires learning to identify a series of ultrasonographic signs indicative of pathology, particularly related to the cardiopulmonary system[4]. Using a few selected ultrasonographic views, anesthesiologists can attain a vast amount of qualitative clinically relevant information (table 2). At present, PoCUS should be applied to address a specific clinical question. It is possible that the future of perioperative medicine will consist of a brief pre-operative scan in addition to, or perhaps in lieu of, traditional palpation/auscultation.

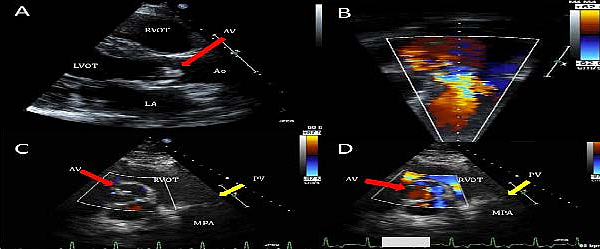

In the perioperative period, PoCUS can provide a wealth of real-time information helping to guide patient management[5]. Envision the ‘on-call’ scenario in which an 86-year-old female arrives for a repair of hip fracture after an unwitnessed fall. She is confused and hypovolemic and a loud murmur is auscultated at the right sternal boarder. In this situation PoCUS may help the anesthesiologist understand the source of the murmur (i.e. severe/critical aortic stenosis vs. mild), the basic overall ventricular function and the general degree of hypovolemia (figure 1). Practically speaking, should the case be delayed for medical optimization, further cardiac evaluation, or to await the presence of a cardiac trained anesthesiologist. Additionally, PoCUS may help guide fluid resuscitation in the pre-operative area prior to proceeding with surgery. It is situations like this where a brief and easily obtainable bedside PoCUS evaluation can aid the anesthesia anesthesiologist’s management decisions.

Numerous studies have highlighted the successful implementation of PoCUS in perioperative management. Canty et. al. report a 54% change in anesthetic management when bedside ultrasound was used as part of the preoperative evaluation in patients with symptoms of cardiac disease or those believed to be at high risk for cardiac disease[6]. Similarly, Cowie et. al. demonstrated a high incident of change of management when PoCUS was used to assess a variety of perioperative issues[7]. PoCUS may be used to augment and enhance traditional physical examination and can be extremely valuable in all perioperative phases.