VOLUME 28, ISSUE 2

Texas Operating Room Demographics, Structures, and Metrics in 2015

Karl Kristensen, MD, PGY-1 Resident, Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine; Mitchell Tsai, MD, MMM, Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Vermont College of Medicine, Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation (by courtesy); George Williams, MD, FCCP, Chief of Critical Care and Associate Professor, Department of Anesthesiology UTHSC-Houston; Carin Hagberg, MD, Joseph C. Gabel Professor and Chair, Department of Anesthesiology, UTHSC-Houston; Steve Boggs, MD, MBA, Chief of Anesthesia and Director of the Operating Room, James J Peters VA Medical Center Associate Professor, Anesthesiology The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Operating rooms (ORs) continue to be an important revenue stream for hospitals throughout the United States. It should come as no surprise that these same ORs also account for a large portion of hospital expenses. In fact, ORs typically account for 60% of a hospital’s revenue stream and constitute 40% of an intuition’s expenses. 1,2 Despite the obvious importance of ORs for hospitals, capacities, caseloads, governance structures, or the anesthesiologists management roles. The literature on this subject is currently limited to New York and Vermont and shows there is no consensus in consistent governance structure. 3,4,5 Building on the previous study performed by the New York State Society of Anesthesiologists , we recently surveyed the membership of the Texas Society of Anesthesiologists to help elucidate the same OR metrics in Texas. The survey consisted of 26 previously validated questions that covered the following topics:

- OR demographics and staffing (district, type of hospital, case volumes and specialty categories, the number of anesthetizing locations, composition of the anesthesia healthcare teams).

- OR management (e.g., first case start and turnover times, utilization rates, staffing ratios, overtime, contribution margin, growth in caseload, and block allocations).

- OR governance structures (e.g. individual, team, nurse-led, surgeon-directed, anesthesiologist-driven, collaborative approach).

At the close of the survey, we had received 60 responses (2%) from 2,900 emails sent to the TSA membership database. We received responses from all 11 districts throughout the state.

The Texas survey suggests that orthopedic surgery made up the largest volume of cases (22%) followed closely by general surgery (20%), both of which are higher than national averages (18.1% for orthopedic and 5% for general surgery). The data for Texas is similar to the results from New York State (20% for both general and orthopedic surgery). When this data is analyzed by district and OR size, interesting trends appear. As demonstrated by Figure 1, there is a large variety in case load distribution by district, with the volume of general surgical cases ranging from 26% (District 8) to 10% (District 3). When stratified by OR size, orthopedic cases make up a larger portion of cases in smaller ORs (0-20 ORs) compared to larger centers (> 20 ORs). Conversely, specialty cases, such as cardiac, plastics, and trauma occur in a higher prevalence in these same larger hospitals. The hospital types could be driving this specialization. For instance, our results demonstrate that the hospitals with the greatest number of ORs are academic centers, compared to smaller centers consisting more of ambulatory surgery centers and community hospitals. Regardless of OR size or district, all of the respondents reported that the ORs are directed by anesthesia personnel.

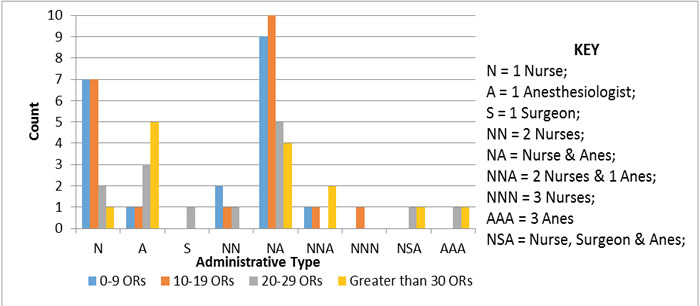

When we examined the data on management structures, we found some interesting patterns. First, smaller centers are more likely to have either a single nurse administrator running the OR, or a team of 2 made up of 1 anesthesiologist and 1 nurse. A team of 1 nurse and 1 anesthesiologist was the most common management structure overall. Figure 2 demonstrates the remainder of the management structure results. While some hospitals had management teams consisting of 3 members, this was disproportionately represented in larger hospitals. Second, individuals who were responsible for managing the ORs at larger hospitals were more likely to have additional management training. However, the majority of respondents did not respond to this question. Third, only 2 hospitals reported surgeon involvement in these teams. When a hospital had a committee governing the OR, surgeons were most often the Chair of the OR Committee with no correlation to the size of the OR.

Responses to the issues addressed by each hospital’s OR committee demonstrated that allocating OR time and improving efficiency were the 2 most important tasks regardless of OR size. There is little agreement amongst the respondents beyond these 2 issues. Figure 3 demonstrates the importance of the other tasks by OR size. In addition, there were differences in the tasks of OR committees and directors. For example, supply management, equipment, and staffing were designated tasks of OR management almost exclusively at smaller hospitals, while budgeting was only a concern of OR management of the smallest (0-9 ORs) hospitals. Finally, all respondents, regardless of hospital size, believed that staff management, OR efficiency, and allocating OR time were important OR management tasks.

Unfortunately, there are several limitations in this study. The response rate is relatively low at 2%. We surmise that this low response rate may be attributed by a self-selection bias and believe that only individuals in a leadership role would respond to the survey. Furthermore, given the overall consolidation of groups in the State of Texas, the number of groups available to respond is relatively limited. Second, the small sample size makes it difficult to determine the significance of the trends and patterns seen with the OR governance structures and the size of the hospital. Despite these limitations, we believe that the survey results that we obtained in this study may be extrapolated to reflect overall trends in OR management, especially considering how the results mirror those found by our colleagues in New York.

With this in mind, we successfully characterized the case load, anesthesiologist involvement, and governance structures of ORs in Texas. The data demonstrates that there is diversity in the number of ORs per hospital, the cases that are performed at these different hospitals, and finally, the governance structures and issues addressed by the governing bodies. We believe that a better understanding of OR governance structures throughout the US can serve to facilitate implementation of the Perioperative Surgical Home (PSH). If anesthesiologists are to help this nation navigate the transition to the PSH model from the more traditional model of surgical care, they will need to become perioperative surgical consultants with expert operational and management systems knowledge. We hope that this study and future surveys will serve as a resource in preparing anesthesiologists for this transition.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

- Saver, C. OR managers’ salaries increase, but so do their responsibilities. OR Manager 2008; 24(10): 9-14.

- Randa K, Heiser R, Gill R. Strategic Investments in the Operating Room (OR): Information Technology (IT) to Generate Rapid ROI and Long-term Competitive Advantage. Health Information and Management Systems Society, August 4, 2009.

- Sieber T. Operating room management and strategies in Switzerland: results of a survey. European J Anaesthesiology 2002; 19(6): 415-423.

- Kristiansen K, Boggs S, Tsai M. New York State Operating Room Demographics, Structures and Metrics in 2015. Sphere 2016, 67(4): 23-26.

- Chen YK, Montagne KA, Boggs SD, Tsai MH. Operating room governance in rural hospitals: Vermont. American Society of Anesthesiologists Conference on Practice Management. San Diego, CA, January 2016.