Volume 25, Issue 2

improvised operating room table.

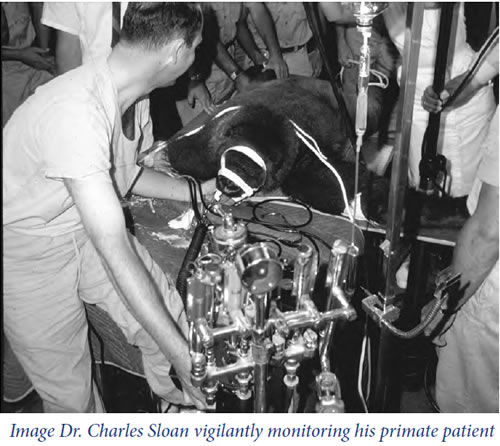

A ratchet-operated mouth opener was placed into the gorilla’s mouth and opened to its maximum extent. It is of interest that the mouth opening was 11 inches from the upper incisors to the lower incisors. The mouth itself was quite deep and at the bottom of this huge cavern you could see the epiglottis, which is a club-like structure rather than a leaf-like structure. The epiglottis was anesthetized with a little topical tetracaine. It was easily elevated with the tip of a No. 4 Guedel laryngoscope blade and the trachea was intubated without difficulty with a size 42-French endotracheal tube at about 5:00 p.m. This is one and a half hours now after the beginning of anesthesia.

Really, the intubation was one of the things that gave us the greatest fear in going out to perform the anesthesia for this animal. We were really concerned whether we would be able to get her intubated, and sure enough, it turned out to be a very simple job.

The endotracheal tube was connected to this old Heidbrink anesthesia machine, then nitrous oxide and oxygen were given, along with methoxyflurane, which was vaporized from a No. 8 jar. The blood pressure was taken with an oversized human blood pressure cuff and found to be 120/40. The pulse rate was 90 and respiratory rate 20.

A nasogastric tube was passed through the mouth and barium was instilled into the stomach. Several films were made by the radiologist in various positions for interpretation, and the films were carried by high speed police pursuit car to the hospital where they were developed and brought back with sirens blowing and lights burning all the way. There was plenty of help in moving the patient from one position to the other. This of course, is a luxury we do not enjoy in the usual hospital. It was demonstrated that the barium did not pass the pyloric sphincter and 1 mg of atropine was given in an effort to relax the pyloric valve and allow the barium to pass in the intestine. This did not work so it was decided to do a laparotomy.

Along about 8:30 in the evening, we noticed a slowly enlarging, swelling of the neck. The swelling became very large, it was crepitant and felt to represent subcutaneous emphysema by Dr. Sloan and myself. Fearful that we had ruptured the trachea, we finally decided to call it to the attention of the veterinarian. He giggled and told us this was the holler pouch or laryngeal sack which gorillas can inflate to give resonance to their voice when they stand up and holler and thump on their chest.

Anatomically, this air pouch extends to the sides of the neck and down over the anterior chest. The origin of the pouch is well above the tip of the endotracheal tube so we were at a loss to explain why it became inflated. Now after five years of consultation with various scientific colleagues, we decided the pouch was inflated by nitrous oxide that diffused out of the blood into this air sack, increasing its volume. At 8:45 p.m., five hours and fifteen minutes after the beginning of anesthesia, the abdomen was shaved and the laparotomy was begun.

A thorough exploration was performed, although no definite physical cause of an intestinal obstruction could be found. A million units of penicillin was instilled into the peritoneal cavity, the methoxyflurane was discontinued and the closure was begun.

I have heard it said by many anesthesiologists, that we have difficulty gaining respect of our surgeon and that many times, surgeons continue to operate in spite of our request to back off a minute or two