Volume 25, Issue 2

David E.Bryant, MD

Economics Editor

The Game of Chicken played as a child in one form or another is immediately recognized without much explanation because it is a metaphor for a set of conditions and patterns that everyone knows already. It was the core of the Cold War’s Brinkmanship where the strategy of escalation to the “Brink” of nuclear war would lead to concessions by the opposing side. An equally important “Game” is the Prisoner’s Dilemma. It describes the frequent dilemma a group of stakeholders find themselves in where resources are being captured and individuals might not cooperate even if it appears in their best interest to do so.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma in its simplest form:

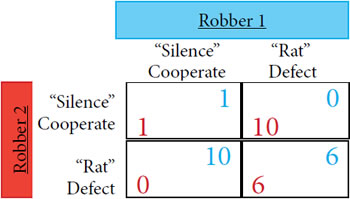

The Police arrest two individuals suspected of cooperatively robbing a bank, but have no direct evidence. They are brought in on lesser charges and placed in different rooms with the intent of getting each to “Rat” or defect on the other. If each stays silent they remain in “cooperation”, and their sentence on a lesser charge is small. If they both “Rat” on each other, each sentence is longer. But if one “Rats” on the other and it is not reciprocated, the “Rat” is free and the “Sucker” goes to prison for the maximum time.

Illustration 1- Prisoner Dilemma Grid, numbers represent years sentenced to prison.

So, what happens? Despite their combined best outcome of 1 year each if they just stay silent or cooperate. Too often one rats out the other or both.

The worst case for the individual is to remain silent while his or her accomplice defects and “Rats” them out (Sucker’s Payoff) illustrated the upper right and lower left squares. For each individual player, the best strategy (Dominate Strategy) is to “Rat” (defect), but the combination of both playing that best strategy leads to the most common outcome. This outcome is the lower right hand box where both robbers are imprisoned for six years.

Practical Applications:

Mutual Cooperation in an Anesthesiology Group:

All members of a group vie for resources. Those resources may be time, money, power/influence, case type or load, research assistants, care team or solo cases, call or no call etc… If everyone in the group cooperated and did their fair share of the work, or worked equally hard, or did their fair share of the hard cases then the group would be in a better place with higher moral, higher income, better service, greater manpower, better longevity and stability etc… All too often, however, defection by individuals to garner a greater share of any one of these resources causes further defection for fear of the “Sucker’s” payoff. However, if the cooperation rate remains high, then all members benefit. The pie actually gets larger.