VOLUME 34, ISSUE 2

Amy P. Woods, M.D.

Medical Director, Parkland Pre-Anesthesia Evaluation Clinic

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Dallas, TX

Russell K. McAllister, M.D., FASA

TSA Newsletter Editor-in-Chief / Academics Editor

Clinical Professor and Chair of Anesthesiology

Baylor Scott & White Health Central Division

Texas A&M College of Medicine

Temple, TX

On the Shoulders of Giants Series: Legends of Texas Anesthesiology Michael A. E. Ramsay, M.D., FRCA: From London to Dallas

For almost half a century, Dr. Michael Ramsay has been a force in Texas anesthesiology. A dedicated clinician, recognized researcher, sought-after lecturer, and fierce patient advocate; there is much to be learned from his impressive personal and professional journey.

Dr. Ramsay was born on February 5, 1945, in Dublin, Ireland, to an English father and Irish mother. At the age of 7, he received a scholarship to attend the Brentwood School, a prestigious private school just outside of London, founded in 1557. He always knew he would be a physician, though he does not remember exactly why. His mother was a nurse, and he admits this might have partially influenced his decision. He attended the London Hospital Medical College (founded in 1775, now known as the Royal London Hospital) in the east end of London, also known as “the dark end.”

After his first semester of medical school, Ramsay found himself at the bottom of his class, which was an unfamiliar and uncomfortable place for him. He set out to change that, and he began to intentionally wake up every day at 4 AM to either study or write. He thus learned a strong work ethic early, and this has allowed him to be quite productive throughout his career. He also credits this experience as teaching him how to balance work with “everything else.”

It was during medical school that Ramsay would meet his future bride as he competed in a rugby match. The United Hospitals Cup is the oldest rugby cup competition in the world, and Ramsay, who played for the London Hospital team while in school, was injured in one of the games. Fortunately for him, Zoe, a physical therapist volunteering at the game, came to his aid, and the two fell in love. Michael and Zoe celebrated their 51st anniversary this year. They have four children: Tara, Kirsten, Mark, and Paul.

At the age of 22, Ramsay graduated medical school with plans to pursue thoracic surgery. As fate would have it, there were no positions available in thoracic surgery for six months, so he took an internship in anesthesiology instead. Ramsay said, “I realized [anesthesiology] was a field that was wide open, with a lot of possibilities for research and change, and I really got into it.”

Since the beginning, patient safety and the overall patient experience have certainly been mainstays in Ramsay’s long and celebrated career. His first paper, written just after his internship, was on the topic of “Preoperative Fear.”3 Not long after, his second published paper called, “Infection Hazard from Syringes,” warned anesthesiologists of the contamination risks of re-using syringes.2

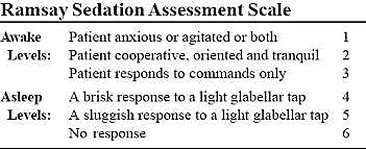

His third publication, and arguably one of his most famous, was titled, “Controlled Sedation with Alphaxalone-Alphadalone.”1 At that time in London, sedation in the ICU was an all-or-nothing phenomenon, and patients could sometimes take days to awaken, if at all. Here, Ramsay recounts the story of how he developed the sedation scale that now bears his name:

“I wondered if we controlled sedation if we might get them responsive quicker, even keep them responsive, but comfortable. And so that was the vision that I put out there, and I just developed a scale out of the air, basically. I just made six points on it. I wanted a stimulus that did not hurt them; I didn’t want them slapping… or pinching the patient. I watched a movie where the cowboys were around a campfire, and somebody wanted to leave the camp with somebody else and not wake anybody up. He came across camp and tapped the guy between the eyebrows. The other guy raised one eyebrow and woke up quietly, and they snuck out of the camp. I thought, ‘That’s what I want! How can I call that area of the face?’ So, I looked it up, and it’s called the glabella. That’s why I called it the glabellar tap.”

And so, Ramsay’s “Controlled Sedation Score” was born. Years later, he recalls attending an IARS meeting in Honolulu, where he saw a poster with reference to the Ramsay Sedation Scale. He soon realized that the “Ramsay” referred to in the poster was him, and his scale was now being used by the anesthesia and critical care community worldwide! Ramsay has since gone on to publish about 200 articles and letters to the editor and has authored or co-authored 30 book chapters during his career.

After completing his internship and residency in anesthesiology, he pursued two fellowships: Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology at the London Chest Hospital and Pediatric Anesthesiology at the Hospital for Sick Children (now known as Great Ormond Street Hospital). In 1974, Ramsay was appointed the youngest ever Consultant Anesthetist on faculty at the London Hospital, a position he only held for three years before moving to the United States.

Although his practice in London was an academic practice, for a small cut in salary, British academic physicians of the day were permitted to do private practice in their spare time, before 8am and after 5pm. He describes his private practice as a “fascinating, fun practice,” where he cared for some of Britain’s elite, including the Royal Family. However, he was working nearly 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and he lamented that he was not home for his family. With four children now, Ramsay began to seek other opportunities, and one such opportunity was in Dallas, Texas. Faced with a big decision, Ramsay was torn. Again, fate would play a role. Ramsay found himself caring for Donald Coggan, the 101st Archbishop of Canterbury, and he explained his dilemma to the religious leader. After four hours of counseling, the Archbishop of Canterbury had some surprising advice, “Mike, you must go. You’ll regret it for the rest of your life if you don’t.”

Ramsay moved to Dallas, Texas, in December 1976. Initially, he worked at many of the area hospitals. Eventually, he and colleagues would create a practice at Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC), and in 1989, he was appointed Chief of Service. Later, he was honored as the first ever physician to serve on the hospital’s Board of Trustees. Of all the achievements during his tenure at BUMC, he notes the successful development of the liver transplantation program to be what he considers the greatest. Baylor was the site of the first liver transplant in Texas and only the fourth program in the United States. The organ recipient was a four-year old girl who suffered from biliary atresia. Ramsay, with his dual fellowships, was perfectly suited to care for this complex case. The full story of this medical miracle is beautifully documented elsewhere and well worth the read.4 “Watching an organ reperfuse,” Ramsay explains, has been one of the most rewarding experiences of his entire clinical practice.

“[At BUMC,] we did lots of research…which is quite unique in private practice. We wrote a ton of manuscripts.” One of those manuscripts Ramsay remembers fondly, as it was a joint project with his daughter, Kirsten, who had only just graduated high school. By this time, BUMC had performed many liver transplantations. Some did well; some did not. Ramsay and his daughter reviewed the database of cases, looking for trends, and they discovered that patients with severe pulmonary hypertension were associated with higher mortality.5

In retirement, Ramsay is finding ways to stay busy. “I’m just wound up,” he laughs. The day following his retirement from BUMC, he was appointed CEO of a non-profit organization, The Patient Safety Movement Foundation. Ramsay believes patient safety has been one of the major areas of change he has seen over his 50-year career. “[When I began,] anesthesia mortality was 1 in 10,000, and we certainly were not doing the types of cases we do now. Today, we take on anybody, after tuning them up, and mortality is somewhere around 1 in 250,000, so anesthesia has gotten much safer… We are ahead of virtually every other specialty in terms of safety.” In Ramsay’s opinion, the next great advancement in anesthesia will be in monitoring. “[We just need to] push the companies to come up with the technology to do what we need it to do.”

Of all the honors and accolades in his lifetime and there have been many, Ramsay notes his family as his most valued accomplishment. “Family first,” is a motto that he lives by. “Success is defined as a happy family. You have to make time for your family, and I’ve always tried to do that.” His advice to young anesthesiologists? “If you really want to do it, be the best you can be. Do not worry about the money. If you worry about the money, you are going to get depressed. Do it because you want to be a physician in anesthesia and be the best you can be.”

Wonderful words of advice from a living legend in anesthesiology – a Texas giant, on whose shoulders we stand.

Sources cited:

- Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BRJ, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadalone. British Medical Journal 1974; 2(920):656-9.

- Blogg CE, Ramsay MAE, Jarvis JD. Infection hazard of syringes. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1974; 46:260-262.

- Ramsay MAE. A survey of pre-operative fear. Anaesthesia 1972; 27:396-402.

- Klintmalm G. The history of organ transplantation in the Baylor Health Care System. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2004; 17(1): 23–34.

- Ramsay MAE, Simpson BR, Nguyen AT, Ramsay KJ, East C, Klintmalm GB. Severe pulmonary hypertension in liver transplant candidates. Liver Transplantation and Surgery 1997; 3:494-500.