VOLUME 35, ISSUE 2

Erin S. Williams, M.D., FAAP

Associate Professor

Department of Pediatric Anesthesiology and Perioperative Pain Medicine

Texas Children’s Hospital

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, TX

Don J. Daniels, M.D., MBA, FASA

Department of Anesthesiology

Baylor Scott and White Temple

Clinical Associate Professor of Anesthesiology

Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine

Temple, TX

Russell K. McAllister, M.D., FASA

TSA Newsletter Editor in Chief / Academics Editor

Professor and Chair of Anesthesiology

Baylor College of Medicine-Temple

Chair-Baylor Scott & White Health-Central Texas

Temple, TX

On the Shoulders of Giants: Legends of Texas Anesthesiology

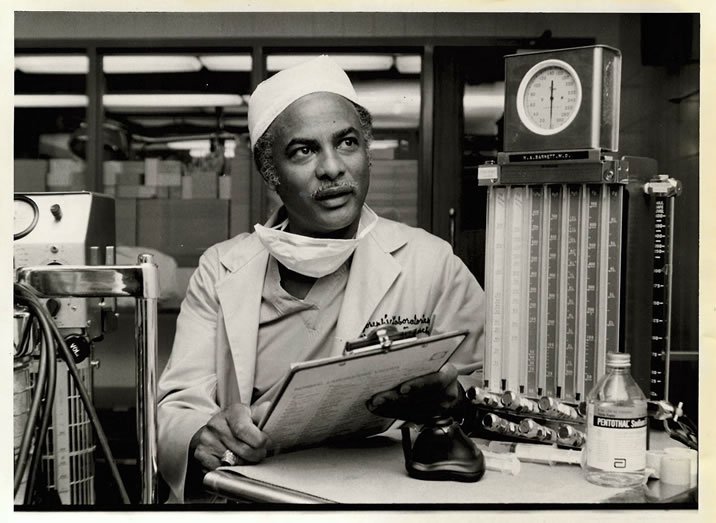

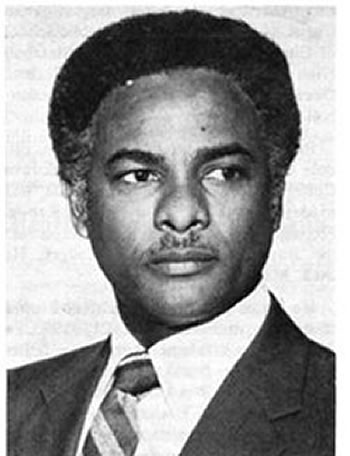

Herman Aladdin Barnett, M.D.

Our latest honoree for the On the Shoulders of Giants series is Herman Aladdin Barnett, M.D. This legend of Texas anesthesiology was brought to our attention because of his far-reaching accomplishments in advancing opportunities in medicine and beyond for African Americans. His role in setting into motion the desegregation of medical education across the state of Texas (and many other parts of the United States) is a story that needs to be told.

We embarked on our journey to explore the life of Dr. Barnett and his noteworthy and tremendous contributions to Texas medicine. We wanted to recognize and honor this Texas trained anesthesiologist, a phenomenal medical doctor, who carried the torch and became the first black student to attend medical school in Texas. This courageous change maker broke down barriers of every type, most specifically the color barrier.

Texas native son who had a dream

On January 22, 1926, Herman Aladdin Barnett was born in the small town of Lockhart, Texas which is located between Austin and San Antonio. He was the only child of Mr. Herman Barnett and Mrs. Lula Searcy Barnett. Dr. Barnett could have been just another statistic, lost to the challenges of a segregationist society, especially given that his father passed away when he was just a toddler. However, his mother and stepfather, the Reverend Sylvester Byars, provided him a supportive environment that allowed this bright young man to thrive. This loving upbringing, coupled with his intense desire to seek new knowledge, helped to lay the foundation for Dr. Barnett’s contributions and successes.

United States Air Force Flight Officer and College Graduate

Dr. Barnett grew up in Austin and eventually graduated from Phyllis Wheatley High School in Austin, Texas in 1943. As required of young men during World War II, he enlisted in the United States military in 1944 and underwent fighter pilot training and eventually became one of the legendary Tuskegee Airmen, successfully completing training at the Tuskegee Army Airfield in Alabama. Dr. Barnett served our country from 1944-1946 as a member of the 332nd Fighter Group of the United States Air Forces during World War II and was honorably discharged as a flight officer in 1946 following the conclusion of the war (1). He continued in his spirit of service and excellence by serving in the medical reserves of the United States Air Force for many years (1).

After completing his full time military service in 1946, he began to pursue his childhood dream of becoming a physician, which fueled his subsequent enrollment at the historically black Samuel Huston College (now known as Huston-Tillotson College), located in Austin where he received his Bachelor of Science (B.S.) degree in chemistry and mathematics, graduating with honors in 1949. This former fighter pilot and new college graduate, who had previously worked as a chemistry assistant and summer school biology teacher while in college, was noted to be extremely gifted academically and was encouraged by his former college professor to fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming a physician. This dream would have been considered seemingly impossible, given the fact that there were no medical schools in the state of Texas that admitted African American students (2). However, Dr. Barnett was the type of person who knew what he was capable of and would not take “no” for an answer.

Trailblazer

In May of 1949, the young and gifted Barnett boldly submitted his application for acceptance into the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), the first medical school in Texas which was established in 1891. Despite already being accepted into the University of Chicago and Meharry Medical College, Dr. Barnett desired to remain close to home and believed it to be his right to attend the only state supported medical school in his home state rather than have to travel thousands of miles away (3). Sadly, just as The University of Texas had worked to uphold segregation by prohibiting the admission of black prospective law student Heman Sweatt in 1946, the institution behaved similarly upon receipt of Barnett’s medical school application. The University of Texas system proposed the option of creating a medical school solely for African Americans rather than desegregate and allow Barnett admission into UTMB. The proposed new medical school would be located in Houston at the Texas State University for Negroes (now Texas Southern University, or TSU), with a timeline for opening in 4 months. The idea that a quality medical education was possible in a segregated non-existent institution that was allocated to receive approximately one tenth of the funding of UTMB set the stage for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to work tirelessly to have qualified African American students admitted into UTMB. This laborious, yet necessary, effort involved preparing and funding lawsuits against the University of Texas for denying access to education for capable applicants solely on the basis of skin color.

Given the impossibility of successfully starting a medical school in less than 6 months and the desire to uphold segregation, the honor student Barnett was conditionally accepted as a student at the Texas State University for Negroes, with permission “to study” at UTMB, under the agreement that he would later transfer to the planned (but nonexistent) TSU medical school, once it opened (it never did open) (3).

Despite enduring hateful, treatment that included having to sit separately from the white medical students and only being allowed to care for black patients at the Galveston Negro Hospital, Dr. Barnett excelled with a positive attitude, notably stating, “…my every resource will be taxed to find even one unfavorable incident “when describing his experience as a medical student at UTMB (4). His academic potential was quite evident; in his first year of medical school, he ranked 7th out of a class of 162 medical students (5).

Of note, the costs of funding a new medical school was insurmountable and the TSU medical school never opened due to a variety of fiscal constraints and there was no pathway to accreditation of TSU for the medical education of Dr. Barnett. Ultimately, the Veterans Administration decided not to subsidize Dr. Barnett’s education at Texas State University due to its lack of accreditation. This made the governmental funding source (the G.I. Bill-education funds for those who served in the armed forces) no longer applicable to Dr. Barnett. Thus, to prevent loss of the funds, he was granted full admission as a student at UTMB in October 1950 (6).

In 1953, after overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles, Barnett became Herman Aladdin Barnett, M.D., graduating with honors as the first African American medical school graduate of the state of Texas.

So many firsts, the impact for future generations

Being the first African American medical school graduate in 1953 in the state of Texas was not the end of Dr. Barnett’s contributions to future generations of African American physicians. He went on to be the first black intern at UTMB and completed his surgical residency 1953-1958. He started a private practice surgical clinic as well. Always welcoming a challenge, in 1968 Dr. Barnett returned to train as an anesthesiologist, completing an anesthesiology residency at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Houston; serving in a variety of leadership roles throughout the Houston community. It was noted by a close friend that Dr. Barnett once indicated that, “he hoped he lived long enough so that it was no longer news when somebody became the first black (person) to do anything (7).” (see Table 1)

Notably, Dr. Barnett also served on the board of trustees for the National Medical Association (NMA) (the non-exclusionary medical association established in 1895 given the American Medical Association’s (AMA) prohibition of membership to African American physicians). It was his unrelenting and confident dedication to African American patients and physicians that prompted him to write the White House and formally invite then President Lyndon B. Johnson to the 73rd Annual National Medical Association Convention August 11-16, 1968, held in Houston, Texas. President Johnson accepted the invitation and addressed the membership stating, “All Americans are entitled to the five freedoms of homes, education, jobs, health, and absence from discrimination; freedoms, each and every black man deserves as much as each and every white man (8).”

Some of Dr. Barnett’s notable “firsts” are listed in Table 1.

| Accomplishment | Year |

|---|---|

| 1st African American admitted to a Texas Medical School | 1949 |

| 1st African American to graduate from UTMB | 1953 |

| 1st African American intern and surgical resident at UTMB | 1953-1958 |

| 1st African American appointed to the Texas State Medical Board of Examiners | 1968 |

| 1st African American President for the Board of Education for the Houston Independent School District | 1973 |

Table 1: Several of Dr. Barnett’s accomplishments that helped break the color barrier.

Dr. Barnett served his fellow man tirelessly. He gave back to not only the medical community, but also to the business and aviation communities. Dr. Barnett served as Chief of Surgery at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Lockwood Hospital, and Riverside General Hospital. He was also a member of Alpha Eta Lambda Chapter Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc. One example of Dr. Barnett’s stellar service was his receipt of the Omega Psi Phi Citizenship Award for excellence in community service in 1968. He was also Chairman of the board and president of the Northeast Houston Investment Corporation, Chairman of Lockwood Professional Group Inc., Vice President of the Bronze Eagles Flying Club (a program that serves to introduce African American youth to careers in the field of aviation)(7).

With such a wealth of talent, Dr. Barnett appeared to ascribe to the scriptural message found in Luke 12:48, “…For unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall much be required…” He had an understanding that he should give back to the community and pay it forward for the opportunities that he had been given. Dr. Barnett also felt strongly that everyone deserved an opportunity to be educated to the highest level one is capable and he took action to try to help make that happen.

The Husband and Father

With his tragic passing on May 27, 1973, at the young age of 47, during an Airshow sponsored by the Negro Airmen International Convention, the medical community and city of Houston had lost a giant. His devoted wife, and 5 young children suffered the greatest loss, yet the Barnett family unselfishly continues to be a positive light and share Dr. Barnett’s story. We sincerely thank his wife Dr. Wylma Lynn Barnett, and children Mr. Herman A. Barnett, Dr. Marcus Duane Barnett, Mr. Keith Davol Barnett, Mrs. Lynn-Etta Kay Barnett-Haney, and Ms. April Michelle Barnett for sharing the legacy of Dr. Herman Aladdin Barnett. One of his sons, Dr. Marcus Barnett recalled his mother, Dr. Wylma Lynn Barnett (a retired education professor at TSU) , telling him, his father “did what he did, because he saw injustice, and had to set things right.” He also recollected how amazing it was to tell his high school teacher that his father was both an anesthesiologist and a surgeon (9)! This was a concept that was previously unheard of. The youngest child of Dr. Barnett, Ms. April Barnett was just 6 years old, that Sunday in May 1973. When asked about special memories of her father, she easily remembered her giant of a father as being “friendly and funny.” She spoke of his innate genius that was evident, even in childhood. His inquisitive brilliance led his mother to give him the nickname, “Tinkerer” because he enjoyed taking things apart and putting them back together. He even built a radio that his daughter Ms. Lynn-Etta Kay Barnett-Haney preserved (10). These are just a few priceless memories that allow us a glimpse into the world of this beloved husband and father.

The Distinguished Legend

Despite his untimely death, his impactful legacy lives on in so many ways. The Herman A. Barnett Memorial Award for Scholarly Performance in the Fields of Anesthesiology and Surgery was established and is awarded to an outstanding medical student at UTMB annually; of note, his son Dr. Marcus Barnett was the recipient of this award in 1984. Dr. Herman Barnett was posthumously awarded the Ashbel Smith Distinguished Alumni Award in 1978. This is the medical school’s highest honor. Additionally, Dr. Barnett was posthumously awarded the 28th Distinguished Service Medal of the National Medical Association by vote of the House of Delegates at the 78th Annual Convention of the NMA in New York City on August 13, 1973 (11). Perhaps most notably, his son Dr. Marcus Barnett followed in his footsteps, attended UTMB for medical school, and chose a life of service in medicine and practices Obstetrics and Gynecology in the Houston area. In the same regard, the next generation continues to model Dr. Herman Barnett’s passion to serve; he has a grandson who is a dentist and a granddaughter who is a surgeon.

Unfortunately, we never had the honor of meeting Dr. Herman Aladdin Barnett. We can undoubtedly say that many who came after him have been direct beneficiaries of his dedication and courageous perseverance. Despite the multiplicity of barriers that existed with educational and societal segregation, Dr. Barnett triumphed. He endured overt and covert racism that included a physical beating that occurred when he was pulled over for a traffic stop (12). The civil rights atrocities that he suffered should cause us all to pause and reflect upon all that he experienced and accomplished so that those who would follow would have an easier path. For that, we remain humbled and forever grateful. Dr. Barnett sought a better future, not just for him, but for every African American child with a dream of becoming a physician. Countless physicians from the past 70 years can say that, without a doubt, they have stood on the shoulders of the giant, Dr. Herman A. Barnett. We have more and achieve more, not only due to our own hard work and dedication, but also due to the shoulders of those who came before us that raise us up so that we can soar to greater heights.

One author (ESW) actually decided to become an anesthesiologist while rotating as a medical student at St. Joseph’s Hospital in 2004, the very institution where Dr. Barnett completed his residency in anesthesiology 36 years earlier. Dr. Barnett’s previous work at this hospital and others made the path to a career in anesthesiology easier for African American students who would follow his path later. It is imperative that we remember and honor every trail blazer who sacrificed so much for future generations that they would never get the chance to meet. In the words of his son, Dr. Marcus Barnett, “He kicked the door open for others to walk through (9).”

To recognize the dedication and service of Dr. Barnett, in 1978, the Houston Independent School District dedicated the Herman A. Barnett Sports Stadium in his honor. Additionally, UTMB formed the Herman A. Barnett Distinguished Endowed Professorship in Microbiology and Immunology in 1997 (13).

Dr. Barnett was active in seemingly every facet of society. The sacrifices that Dr. Barnett made have led to UTMB being one of the top producers of African American graduates. What was once a seemingly insurmountable wall of impossibility is now demolished because of Dr. Barnett. By 1968, all medical schools in the United States had abolished their segregation policies (2). The Texas Society of Anesthesiologists recognizes and honors Dr. Herman Aladdin Barnett for his commitment to life-long service by bestowing membership posthumously into the Texas Society of Anesthesiologists (TSA). Our society, our state, our country, and even our world, is better because of the change that Dr. Herman Aladdin Barnett believed in, pursued, and, ultimately, accomplished. It is very unfortunate that his life was cut short at such a young age, however, he accomplished so many impactful things in life and medicine during his lifetime. Therefore, it is a pleasure to honor him as a legend of Texas anesthesiology and all of medicine.

Sources:

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/barnett-herman-aladdin-iii

- Gamble VN. Dr Herman A. Barnett, Black Civil Rights Activists, and the Desegregation of The University of Texas Medical Branch in 1949: “We Ought to Go in Texas and I Don’t Mean to a Segregated Medical School”. JAMA InternMed. 2023;183(3):255–260. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6700

- Negro war vet to attend medical school. Galveston Tribune. August 24, 1949:1.

- Correspondence from HA Barnett to JHMorton, November 19, 1949. In: Papers of the NAACP, part 03: The campaign foreducational equality. Located at: Series B: Legal department and central office records, 1940-1950, discrimination at Texas StateUniversity, folder 001512-004-1090,legal file, group II, schools, folder 001512-004-1090, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- Correspondence from E Griswold to T Marshall, March 17, 1950. In: Papers of the NAACP, part03: The campaign for educationalequality. Located at: Series B: Legal department and central office records, 1940-1950, folder001512-016-0534, Library ofCongress, Washington, DC.

- Report for September 1950, special counsel, Southwest Region NAACP, October 31, 1950. In: Papers of the NAACP, part 25:Branch department files. Located at: Series A: regional files and special reports, 1941-1955, folder 0014489-009-0011, Library ofCongress, Washington, DC.

- The SPHINX | Summer 1973 | Volume 59 | Number 3 197305903

- Whittico JM. Close “the medical gap”. President’s inaugural address, National Medical Association. J Natl Med Assoc.1968;60(5):427-432.

- Personal correspondence with Marcus D. Barnett, MD in June 2023

- Personal correspondence with Ms. April M. Barnett in June 2023

- Cobb WM. Barnett 28th NMA distinguished service medalist for 1973. J Natl Med Assoc. 1973;65 (6):537-538.

- https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1220779/

- https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/barnett-herman-aladdin-iii-1926-1973/